Does Esther Crawley’s latest research really tell us anything about the prevalence of pediatric CFS/ME?

After a quiet time over the holidays and into the new year, ME/CFS has been back in the news again. This time the coverage has in many ways been rather helpful. Dr Mark Porter, writing in The Times painted quite an accurate portrait of the condition: usually starting after an infection; involving numerous symptoms rather than only fatigue; the fatigue itself “persistent and recurrent”; and “exacerbated by physical or mental exertion”. There was even a description (though not by name) of the all-important post-exertional malaise. Pacing was also well described: “some of the strategies are counter-intuitive”, “it is important to avoid the boom-and-bust cycle”, only the exhortation to avoid daytime sleep seemed to me to be off the mark: in some situations this is a useful strategy to restore natural rhythm but in my experience as a patient it’s not always feasible or desirable. Nevertheless I liked Dr Porter’s perspective on the possible psychological repercussions of having ME: “feeling awful for months on end will dampen the spirits of the hardiest person” and severe ME at least gets a mention: “when severe it can leave victims housebound and often bedridden (the worst cases require hospital treatment)”. Not that the hospital is likely to have a clue what to do about it but at least there is some acknowledgement of severity.

The piece on the BBC News website focused more on the new study from the University of Bristol which served as the trigger for this latest splurge of publicity. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome at Age 16 Years claimed that the prevalence of pediatric CFS was 1.9% in 16-year-olds, higher than previously thought. The BBC article rounded this up to 1 in 50 and contrasted it with the 1 in 1000 (it said) who are actually diagnosed. Hmm.

The study also claimed that CFS affected almost twice as many girls as boys at age 16 and was more likely to affect children from disadvantaged backgrounds. According to the article, the study authors said this dispelled the commonly held view that CFS/ME was a “middle-class” illness, or “yuppie flu”.

I think I would dispute the fact that this is a widely held view any more (except perhaps among journalists), most of the general population having either forgotten about yuppies or being too young to have heard of them at all. But I suppose it is a useful enough finding – if it can be trusted, that is, but more of that in a moment…

A couple of days later, there was also a feature on BBC Radio Four’s Woman’s Hour (still available on catch-up at the time of writing). A young patient called Kirstie did an excellent job of describing her efforts to manage the illness: “You need to admit that it’s there.” “You need to give in to it in order to stand up to it.” “The road to recovery is extremely difficult.” Unfortunately she also gave the impression that you could defeat the illness through sheer determination. Sad to say some determined people do not recover. But Kirstie spoke so well overall that it seems a bit mean to labour this point.

Also on Woman’s Hour was the lead researcher in this new study, the pediatrician Esther Crawley. Dr Crawley is not all that popular with many ME patients, principally because of the Smile Project which aims to test the Lightning Process on children. As the Lightning Process involves a GET-like approach where you ignore your symptoms and press on regardless, many feel it is wrong to put children at risk in this way.

Nevertheless I was pleasantly surprised by her performance on the programme. She made a distinction between the 40 to 50% of teenagers who say they feel tired and the “overwhelming fatigue of CFS which stops you enjoying a normal life”. This was, she said, “very different from normal tiredness”. She added “people stop dismissing it when they see someone they know go through it”. She talked about the need to cut back on how much you do on your better days and try to have a consistent level of activity day to day.

The devil is in the detail of course but that all seemed sound enough.

Yet there were also some warning bells. She said that people have disabling fatigue which is usually associated with one other symptom such as unrefreshing sleep, memory or concentration problems, severe headaches or pain. I italicized a couple of words for a reason there, because all of us with ME tend to have a number of such symptoms, not just one. I began to wonder what diagnostic criteria she had used for the study.

After a brief discussion on Twitter caused me further concern, I decided I had better take a proper look at the paper. What I found was rather startling. It turns out that no established criteria were used at all, neither were any doctors involved in making a diagnosis. The whole thing was done by children and their parents filling in questionnaires.

I checked back with the articles I had seen and the radio show. The only one that mentioned this was the BBC web site but I had overlooked it: “The diagnoses of the condition in the study were based on responses to questionnaires sent to teenagers and their parents, and were not made by a doctor.” There you are. You have to read the small print, only sometimes, as with The Times and Woman’s Hour in this case, the small print isn’t there.

This was a big study, part of the Children of the 90s project which has followed almost 14,000 children who were born in that decade as they have grown. Almost 6,000 children were involved in this present CFS study. The paper says “it is important that the uncertainties regarding the population prevalence of pediatric CFS are resolved’. Such a massive project must indeed have seemed like an opportunity to do exactly that – and yet the more I read the study, the more it seemed to me that its reported conclusions could not be trusted.

One of the main problems is that there does not seem to have been any attempt to exclude other conditions which might have produced fatigue in these children. In most research studies, there would have been a medical examination and appropriate testing. Here, no doctors were involved and – with the exception of depression – it does not seem as though the questionnaires even inquired about other conditions which might already have been diagnosed. As for depression, the children were asked about their feelings and the researchers published a secondary figure which excluded those with depressive symptoms. This brought the prevalence of CFS at age 16 down from 1.9% to 0.6% – quite a difference – but this awkward complication wasn’t mentioned in the media, just the headline figure of 1.9% – or, as the BBC put it, 1 in 50.

Nor was there any attempt to determine either the nature of the fatigue or whether symptoms other than fatigue were present. It is important to realize that a) the fatigue in ME is of a particular kind, made worse by (often very modest amounts of) activity, b) other symptoms such as cognitive problems, pain, unrefreshing sleep and many others are also present and c) there is invariably post-exertional malaise whereby symptoms in general become worse after activity, often with a time delay.

There was no attempt to investigate any of this. The parents were simply asked if their child had been “feeling tired or felt she/he had no energy” and whether this had affected their education and activities.

Even the commonly used Fukuda diagnostic criteria require the presence of four out of eight named symptoms (in addition to fatigue) to be present for diagnosis, while the NICE guidelines need post-exertional malaise and one of ten other named symptoms. Many patients and researchers regard these criteria as unduly broad, producing a heterogeneous population which encompasses conditions other than ME, but the parameters used in this present study are broader still, and seem to define simply ‘chronic fatigue’, not ME or even CFS. This is not the same thing at all.

Apparently Dr Crawley and her team carried out a similar, smaller, study previously. This involved sending questionnaires to the parents of almost 2,000 13-year-olds and resulted in a prevalence rate of 1.3%. On that occasion the condition was indeed described as ‘chronic, disabling fatigue’, not CFS. The reason they gave for this was that they “had only parental report of fatigue”.

In the new study, questionnaires were sent not only to parents but also to the children. The latter were Chalder Fatigue Questionnaires, and those children who had qualified as having CFS according to the parental questionnaire were nevertheless reclassified as not having the condition if they scored <19 (of 33) on the CFQ. This appears to be the same cut off point as was used in the PACE Trial.

The CFQ does not test for the PEM which is so characteristic of CFS yet Dr Crawley and her team apparently believe that this extra test makes all the difference. Because the children have scored 19 or over in the CFQ, they say, they can now be classed as having CFS rather than just ‘chronic, disabling fatigue’.

This seems to me to be less like genuine science than ‘making it up as you go along’. The CFQ does not distinguish CFS from other forms of fatigue. It tells us nothing about PEM, and next to nothing about the other symptoms present in CFS. This appears to be yet another half-baked way of defining CFS to add to the many which already exist, embodied in a collection of criteria which cause more chaos than enlightenment.

Far from ‘resolving the uncertainties regarding the population prevalence of pediatric CFS’, it seems that this study simply adds to the confusion. Really, why did they bother?

In contrast to Dr Crawley’s confident pronouncements on Woman’s Hour, the text of the study more or less admits that its results are unreliable. “The children in this population based study were not assessed by a physician,” they accept, “and our classification was not subject to clinical verification. It is therefore possible that parents and children reported significant levels of disabling fatigue that was caused by another disorder. The most likely alternative diagnosis in this group is depression.”

In view of this, would it not have been better to highlight the figure of 0.6% instead: the greatly reduced prevalence figure once those children with depressive symptoms were removed? Especially as the Fukuda and Canadian criteria both exclude for major depression – and even the Oxford criteria, the psychiatrists’ favourite – exclude for bipolar depression. But Dr Crawley and her team argue that this result would have been ‘almost certainly too low’.

So perhaps, on reflection, it might have been better just to admit that after all that expense and effort, they’re none the wiser what the prevalence rate might be.

Just a couple more points before I move on. The report refers to three previous studies reporting a ‘clinician-verified’ CFS prevalence of 0.1-0.5%, while their own previous result for ‘chronic disabling fatigue’ was 1.3%. They say: “this discrepancy is almost certainly a consequence of referral pathways and barriers to accessing clinical services”. But could it not also be a consequence of many of the cases of ‘fatigue’ not being due to CFS at all?

And incidentally, comparing the present headline prevalence of 1.9% for so-called CFS with their previous figure of 1.3% for ‘chronic disabling fatigue’ strongly suggests that the former figure is ‘almost certainly too high’.

So if this study is as inadequate as it appears to be, what does it matter? If the government thinks the prevalence of CFS is greater than it really is, might that not at least lead to extra investment in research?

Leaving aside the fact that what we patients really want to know is the truth, you have to ask what kind of research this study might prompt. Dr Crawley and her team conclude their paper with: “further research is also needed to investigate the extent to which psychological problems and life difficulties predate or follow CFS. This aspect of adolescent CFS, in particular the role of depression, requires in-depth analysis using repeated measures of mood and fatigue”.

So, on the back of the present study, they see themselves using ME/CFS research money to investigate the role of depression and other psychological factors in the condition. Presumably they would argue that this is very important because according to their study the majority of children with CFS were also deemed to have depression. Best to set aside the distinct possibility that those children – or at least a good proportion of them – had depression instead of CFS, because that would spoil the plan.

They also think that “future research should examine the type of fatigue experienced by children and its different phenotypes.” I can’t help thinking it would have been more useful if they’d paid some attention to that on the present occasion.

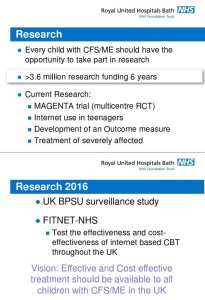

I am grateful to @maxwhd on Twitter for this poster advertising upcoming research from Dr Crawley’s team:

Apparently they have been given £3.6 million in research funding and they think every child with CFS/ME should have the opportunity to be researched by them. Personally, I just wish they could be researched by somebody with a better understanding of ME.

As patients, carers and parents, we are desperate to see research make progress and produce some effective treatments, yet the battle to understand the condition is hampered not only by its inherent complexity but by an entirely man-made muddle of names and diagnostic criteria. When a prominent clinician and researcher in receipt of £3.6m worth of research money seems only to focus on one symptom, ‘fatigue’, and is not overly bothered by the exclusion of other diagnoses, it is hard not to get frustrated.

Note: I realize I’ve used the terms ‘ME’ and ‘CFS’ more or less interchangeably and in rather muddled manner in this post and I apologize for that. In previous posts I’ve mainly referred to ‘ME’ but Dr Crawley’s research paper uses ‘CFS’ so this time I’ve mainly used that. For what it’s worth, I think ‘CFS’ is a rubbish term which only spreads confusion and we’d be better off without it, but for the time being we’re stuck with the mess. Although the paper discussed in this post refers to ‘CFS’, Dr Crawley also referred to ‘ME’ on Woman’s Hour and I notice her poster refers to the NHS standard ‘CFS/ME’. None of which would bother me greatly if she hadn’t mixed them up with generic chronic fatigue.

Another good piece of careful unpicking of the facts behind the hype. It is extraordinary how people who are supposed to be expert in psychology, are completely blind to the fact, that the most depressing thing to people with M.E and other ‘MUS’ diseases, is these psychologists, themselves, for the extreme–to some, life long–number of years that they have been allowed to hold up real medical research into this illness: and for the way they seem set to prevent it–in the UK at least–for ever!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dr Crawley is actually a pediatrician but judging by this paper you could be forgiven for thinking she’s a psychologist! Yes, all the biopsychosocial research which goes on in this country is indeed holding things back, not least via the finely honed grip on the news agenda which goes along with it. I suspect that even the constant repetition of ‘once dismissed as yuppie flu’ is a part of that. What words stick in the memory when you’ve heard that phrase? ‘Dismissed’ and ‘yuppie flu’. Job done.

LikeLike

Great blog thanks. To reiterate and discuss some of the points you highlight…

It’s perfectly OK for researchers to investigate fatigue (of known or unknown cause/etiology), but it’s not OK to present misleading research and to confuse the medical establishment and the public by conflating fatigue with the specific diagnosis of CFS or CFS/ME or ME. A diagnosis of CFS/ME in the UK (as per the NICE guidelines) requires specific characteristics to be present (e.g. post-exertional exacerbation of symptoms with typically delayed onset) and exclusion from a CFS diagnosis is required if the symptoms can be explained by other conditions.

There are a myriad of reasons why teenagers may be fatigued, including having: another (undiagnosed) disease; chronic stress; sleep issues; a psychiatric illness; an over-enthusiastic social life (e.g. late night partying or through-the-night computer use); or being: victims of bullying at school/college; victims of domestic violence or abuse; or engaging in: cannabis abuse (alcohol abuse and use of some other types of drugs excluded responders from a CFS diagnosis in this study); etc. etc.

The research may have been useful if it was properly reported and characterised, but it is misleading in its current form. Not only has a formal diagnosis of CFS not been made, but the criteria, used for the (informal) CFS diagnosis, are novel and do not represent an internationally recognised diagnosis of CFS. An amendment should be made to the published paper to clarify that the study does not investigate CFS.

One other point is that although a self-report Chalder fatigue score of <19/33 was used to exclude an individual from a diagnosis, this was only where data was available (i.e. if the teenager had returned the questionnaire) otherwise any level of fatigue was included for a diagnosis as long as it had persisted for six months, disrupted normal leisure activities "quite a lot" or more over the past year, and had caused at least one period of absence (e.g. as little as a half-day or less) from school over the past year. The Chalder fatigue questionnaire applied only to any period of fatigue during the past month, and not necessarily a current episode of fatigue.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for expanding on things, Bob. I didn’t have space to cover all the details. Yes, as you say if this was presented as a study of chronic fatigue it would not be a problem. What is so misleading is that it claims to be a study of CFS – and indeed, in the media, of ME – which it simply isn’t. The spin with which these dodgy studies are presented to the world is the most objectionable thing of all. The conclusions are presented as plain fact. Even the admission of uncertainty which appears in the paper itself goes unmentioned in the media coverage.

LikeLike

Another well written post, thank you.

why would Dr Crawley want to create the impression that patients come from poorer backgrounds? Ah, I know, it fits in with her narrative that it is a behaviour disorder related to such things as childhood trauma. I haven’t looked at the paper yet but I suspect there are other interpretations of the data, for example, having a sick child often means one of the parents having to cut down or quit their employment, with the obvious effect that household is now poorer. Also wealthier families may be more likely to avoid such doctors as Dr Crawley in favour of experts who treat ME/CFS as a physical disease, which of course costs money as you can’t get this on the NHS. Also the disease sometimes appears to run in families so a parent may be incapacitated from work, again reducing family income. These three thoughts of the top of my head, I am sure there are other factors you would need to consider and I suspect when you do The truth ends up that ME/CFS can and does hit anyone, it doesn’t care how rich or poor you are.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I suppose it is always possible that Dr Crawley has a genuine open-minded scientific interest in the socioeconomic background of those with ME/CFS! I’m afraid it is a measure of the estimation in which we hold such researchers after all that has happened that we scarcely give such a possibility a second thought. It is a sad state of affairs. Yes, I’m afraid that, like you, I suspect there is an underlying agenda. The paper reads: “future research should… investigate potentially important etiologic factors that might explain

the association of fatigue with family adversity. Further research is also needed to investigate the extent to which psychological problems and life difficulties predate or follow CFS.” It is hard not to think of it as a meal ticket.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How can a chronicle sick poor person ever improve? With the wrong treatments being pushed on them? You only make health issues harmful. You need to wise up! To the harm you do. Think about it for M.E. If you don’t live it! Don’t tell someone who does. They only know to well that PEM is debilitating painful on every level. Rest is the only thing to do at that time. Not pushed to exercise.

LikeLiked by 1 person